When it comes to studying subgenres of speculative fiction, we find some of them fall neatly into hierarchies and groupings. High and low fantasy are obviously major aspects of the fantasy genre, while hard and soft science fiction are the same for science fiction. Another grouping of genres that seems like it should be as simple is the ‘punk genres, a growing subset of speculative fiction with labels that end in “punk”.

In this essay, we’ll explore just what makes something ‘punk and take a closer look at some of the more prominent examples of ‘punk fiction.

What is ‘Punk?

Despite the shared naming convention, we sometimes find more differences between these genres than similarities. The various ‘punk genres of speculative fiction can be surprising, amusing, and thought provoking. They often blur the lines between different types of speculative fiction. Many of them share common themes such as antiauthoritarianism and disestablishmentarianism. The commonality of these themes is largely responsible for the use of the word “punk” in their names. The views expressed in early cyberpunk works—which birthed the entire movement—reflected those of the punk subculture of the 1970s and 1980s.

But what, exactly, is ‘punk fiction? It is a family of loosely related speculative fiction subgenres that often say, “To hell with the rules.” In other words, they tend to do their own thing. Despite this bucking of the rules and the wide variety of subgenres using the ‘punk moniker, there are still certain aspects that tie together these genres.

I would define ‘punk fiction as a group of speculative fiction genres which strive to move outside the boundaries of classical science fiction and fantasy norms, often focus on the effects of technology on society or explore a fictional society or alternative history with anachronistic levels of technology—sometimes referred to as ‘retrofuturism’—and typically address social issues with an anti-establishment perspective.

The Punk Revolution of Tomorrow

Although one might think all ‘punk genres fit into a single bucket, we can make some subdivisions to help us understand the various genres’ similarities and differences. I haven’t seen an official hierarchy dividing these before, so there aren’t any handy labels to shelve them with, but the groupings will reveal themselves to be very intuitive. First among these are genres that reside very much in the realm of science fiction, in that they deal with the future of humanity and explore the advances of both technology and society. These ‘punk genres often criticize authoritarianism and runaway capitalism. They also paint a bleak picture of a future where humanity is so reliant on technology that we’ve lost our independence. Some might even argue we’ve already caught up to some of these themes in our own reality.

Cyberpunk

A subgenre of science fiction, cyberpunk is the father of the ‘punk genres. Cyberpunk works usually examine a near-future Earth where technology—especially computers and the internet—has become the backbone of society, but where that same society has broken down at some level, often as a result of capitalism becoming the dominant authority. Cyberpunk stories usually take place in dystopian settings with corrupt governments often run by megacorporations. Neuromancer by William Gibson, published in 1984, was the first piece of fiction to be codified as cyberpunk. Although it was not the first example of the genre, it is considered by many to be the book that defined the movement.

Borrowing elements from the hardboiled and noir genres of crime fiction, cyberpunk stories often involve either a criminal investigation or and underground movement rooting out corruption in the government or ruling corporations. Common themes may include modern humanity’s reliance on technology, the blurring of lines between reality and virtual-reality, overpopulation, and the moral implications of self-indulgence.

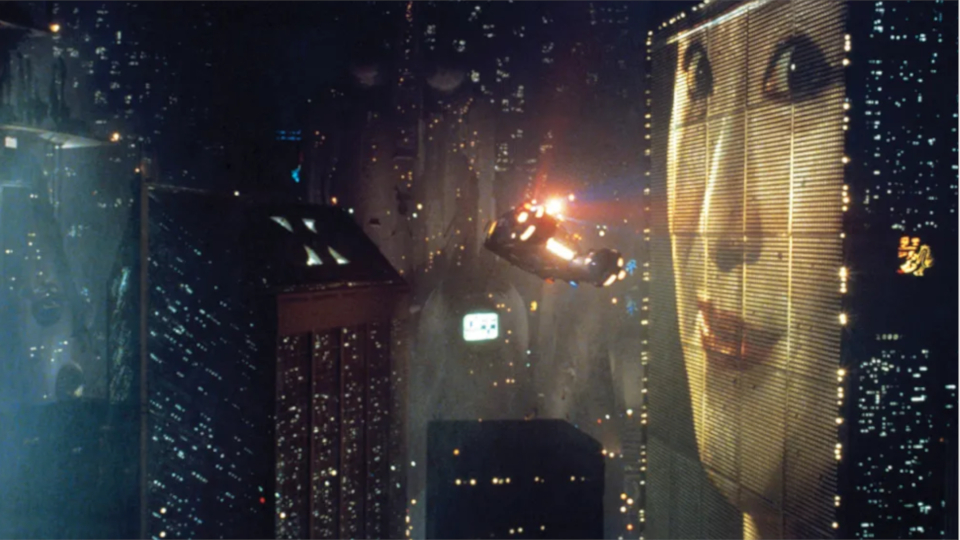

A notable precursor of the genre is Do Androids Dream of Eletric Sheep? by Phillip K. Dick (1968). In fact, the film adaptation of the novel, 1982’s Blade Runner, did much to cement the imagery of cyberpunk in the collective consciousness. Other notable examples of cyberpunk fiction include Diaspora by Greg Egan (1997), Altered Carbon by Richard K. Morgan (2002), and Ready Player One by Ernest Cline (2011).

Post-Cyberpunk

Post-cyberpunk borrows worldbuilding elements from cyberpunk—showing characters interacting with technology in their every-day lives—but sheds the dystopian future for a more hopeful vision of a technologically-centrist future. This may or may not be a utopian society, but at the very least will be more optimistic than the typical cyberpunk story. Also, the characters are often more functional members of society rather than reluctant anti-heroes, social outcasts, or outright criminals. Post cyberpunk stories also show an evolution of our relationship with technology. When cyberpunk first came about, the internet revolution was just cresting the horizon and the future impact it would have on humanity was unclear. Firmly cemented in the digital age as we have become, post cyberpunk authors often have a less reactionary perspective on the connected world.

Examples of post cyberpunk fiction include The Diamond Age by Neal Stephenson (1995), Holy Fire by Bruce Sterling (1996), Glasshouse by Charles Stross (2006), Rainbows End by Vernor Vinge (2006), and Infomocracy by Malka Older (2016).

Biopunk

Biopunk is very similar to cyberpunk in themes of dystopian near-futures ruled by megacorporations and totalitarian governments, but rather than focusing on the implications of information technology on future society, it examines the possible corruption of synthetic biology and genetic engineering, sometimes going as far as exploring the potential horrors of eugenics.

Paul Di Filippo’s collected short fiction anthology Ribofunk (1996) is a prominent example of the genre, and he himself referred to The Island of Doctor Moreau by H.G. Wells (1896) as a precursor to the sub-genre. Other notable examples of biopunk include Jurassic Park by Michael Chrichton (1990), Starfish by Peter Watts (1999), and The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi (2009).

Nanopunk

A relatively new entry into the ‘punk world, nanopunk is similar to cyberpunk and post-cyberpunk. These stories may range from dystopian to utoptian. Rather than investigating the potential applications of information technology, nanopunk explores the potential abuses and uses of nanotechnology—that which manipulates matter on a molecular or smaller scale.

Examples of nanopuk stories include Queen City Jazz by Kathleen Ann Goonan (1994), Tech-Heaven by Linda Nagata (1995), and Nexus by Ramez Naam (2012).

Retrofuturism in Punk Fiction

While all our prior examples look to the future of humanity, a large subsegment of punk fiction looks to our past. Technology also plays a major role in these stories, but instead of exploring what might be, they ask, “What might have been?” Retrofuturism explores the potential advances of future technology from the perspective of a past age. While we might envision a future full of robotics, artificial intelligence, and space travel, how might somebody in the Victorian era or the 1930s have envisioned the future?

Clockpunk

Clockpunk is similar to, and considered an offshoot of, steampunk. Rather than focusing on the possibilities of steam-powered technology of the Victorian era, however, clockpunk takes things back a step and speculates on the potential of the Renaissance and Baroque eras. The main source of mechanical energy during this time was gear-driven machines, which often stored energy using a spring that could be wound by hand.

Machines in this genre are often beautifully decorated, matching the styles of the eras upon which it is inspired. Often, the energy output of certain machines may greatly exceed the seeming level of input, such as winding the mainspring of a device. Rather than resorting to handwavium to explain this, many authors will incorporate some sort of practical magic application.

[Clockpunk] can be very fun to write in because one can easily limit the powers available while still going absolutely fantastic with the imagination.

Stephen Coghlan

Steampunk

Steampunk is one of the first anachronistic offshoots inspired by cyberpunk. In fact, the name steampunk was a tongue-in-cheek reference to the cyberpunk genre founded only a few years earlier. Often taking place in a Victorian or American “wild west” setting (with the latter sometimes referred to as Cowpunk or Cattlepunk), steampunk embraces the steam-powered technology an aesthetics of the nineteenth century while extrapolating on possible applications of such technology to modern or futuristic devices. It may also take place in a futuristic setting where steam power remained the main method of energy production.

The term “steampunk” was coined by science fiction author K.W. Jeter in a letter to Locus magazine in 1987. He used this term to define his own work on Infernal Devices (1986) among works of contemporaries that were inspired by Victorian science fiction such as the works of H.G. Wells. There is also a subset of steampunk fiction that involves fantastic elements, such as magic, referred to as gaslamp or gaslight fantasy.

Other notable examples of steampunk fiction and gaslamp fantasy include Leviathan by Scott Westerfield (2009), The Alloy of Law by Brandon Sanderson (2011), The Aeronaut’s Windlass by Jim Butcher (2015), and Storm Glass by Jeff Wheeler (2018).

Teslapunk

Teslapunk is often set in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, covering the Victorian and Edwardian eras. While there’s some overlap with steampunk as far as the time periods involved, the difference is that most or all technological applications are powered by electricity. Named for famed physicist Nikola Tesla, this genre explores the what ifs of an industrial revolution fueled by clean electricity rather than coal power.

Teslapunk settings usually involve an abundance of free energy and empowerment of the masses, bucking the societal norms of the industrial revolution. During this time, there was a monopoly on fuel sources and the common people suffered under oppressive labor standards. In the empowered settings of teslapunk stories, alternative structures of society during the period are often explored.

Dieselpunk

Dieselpunk brings the perspective of retrofuturism forward the early twentieth century, ranging from the waning of World War I through just after the end of World War II. As the name suggests, the setting leans heavily on applying science fiction elements to the internal combustion engine technology which revolutionized all aspects of society, most notably warfare, during this age. Setting-appropriate themes include a grimmer outlook on humanity and a focus on the wars of the era.

Other than being defined by its temporal setting and focus on diesel technology, dieselpunk also incorporates many pulp-fiction-inspired tropes such as pulp adventure, noir, and weird horror. In fact, the term “weird world war” is a popular subgenre of fictional situations set during World War II incorporating elements of the supernatural. While dieselpunk and weird world war stories often exist independently of one another, overlap between the two is not uncommon.

Further, Dieselpunk can be subdivided into two primary themes: Ottensian and Piecraftian. Ottensian, named for author Nick Ottens, explores the utopian optimism of the roaring twenties. In these stories, war does not damper the spirit of progression and prosperity, nor is there an early 20th century economic collapse. Alternatively, Piecraftian dieselpunk—named for the author who coined the term, Piecraft—is the gloomy and dystopian side of dieselpunk. Often, Piecraftian stories take place in a post-war period where either the second world war has devolved into a cold war, continues to be fought, or was won by the axis powers.

Some notable examples of dieselpunk fiction include Fatherland by Robert Harris (1992), The Company Man by Robert Jackson Bennett (2011), Ack-Ack Macaque by Gareth L. Powell (2012), Silent Empire by Bard Constantine (2015), and Tin Can Tommies: Darkest Hour by Mark C. Jones (2018).

Decopunk

Decopunk is the shiny, optimistic, stylized cousin to dieselpunk set in the same time period of the 1920s through the 1940s. Author Sara M. Harvey helped to define the sub-genre, stating in an interview that “DecoPunk is the sleek, shiny, very Art Deco version; same time period, but everything is chrome!”

Arguably, one could say that this sounds very similar to Otessian dieselpunk. As both terms are fairly recent and both sub-genres are still relatively small, the future will show which affectation will become more generally accepted or where the line between the two lies. It seems to me that decopunk would be less involved with the great wars of the time and more with civilian life, possibly even showing an alternative history where the horrible atrocities of the world wars never even happened.

Atompunk

Atompunk is generally set during the Cold War era and incorporates speculative applications of nuclear technology. Things such as robots, powered armor, and even cars powered by nuclear reactors are commonplace. The Fallout series of video games is probably the most popular example of atompunk (although this takes the nuclear retrofuturism of the 1950s and thrusts it into a nightmarish, post-apocalyptic future). Often, works in this genre will include an aesthetic of 1950s style retrofuturism and explore the potential gains or downfalls of atomic age technologies.

Punks of the Fantastic

While most punk genres lie firmly in the realm of science fiction and focus on exploring the effects of technology on human development, either in the future or an alternative past, some punk genres add liberal amounts of the fantastic into the mix. Most of these genres fall comfortably under the umbrella of science fantasy, a genre which blends aspects of science fiction and fantasy. One of these genres was already mentioned above: gaslamp fantasy, the fantastic cousin of steampunk. Below are a few more prominent examples of punk genres that delve into the fantastic.

Magepunk

Magepunk—also sometimes called Dungeonpunk, Arcanepunk, or Magicpunk—is defined by a setting where technology and magic coexist and are readily available. The applications of these technologies can range from what might have been accomplished from the inception of gunpowder to industrial, modern, or futuristic technologies, but its operation is either partially or entirely dependent on magic as a catalyst and the settings are usually more reminiscent of traditional fantasy settings such as those inspired by medieval Europe.

The most prominent representations of this genre can be found in tabletop gaming, such as the Eberron setting in Dungeons and Dragons, the tabletop wargame Warmachine, and in the Magic: The Gathering setting of Kaladesh.

Dreampunk

Dreampunk is probably the most esoteric of the ‘punk genres, and therefore is the hardest to define. In its most basic form, dreampunk can consist of a story that entirely takes place in a dream. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865) can retroactively be considered an excellent example of dreampunk. Also, the 1939 film adaptation of Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz can be considered dreampunk (although the original novel from 1900 did not contain the “it was all a dream” ending).

On the other hand, dreampunk can consist of any story where the imagination or psyche has power over reality. A protagonist able to conjure objects or other characters into existence through pure imagination might be in a dreampunk story. Finally, dreampunk may focus more on the state-of-mind of the characters than the reality in which they live, as elements of Jungian psychology are often explored in these stories. Also, a character’s perception of reality may differ from the reality itself through some sort of mental disconnect. Dreampunk elements can appear in other forms of fiction, often without even being noticed. The dream-walking scenes in Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series is a good example of this.

The best advantage to dreampunk is that it’s ageless. You can have anyone, anywhere, doing anything. Now, that also lends a problem to the creator. How do you limit the possibilities, or what rules will one set in place?

Stephen Coghlan, author of the amazing dreampunk novella Urban Gothic

Elfpunk

Elfpunk is speculative fiction in a contemporary or futuristic setting that includes creatures of myth and legend such as elves, dwarves, and dragons. By some stricter definitions, this genre incorporates elements of Celtic and Norse faerie myth in modern urban settings. The popular tabletop role-playing game and the associated books and video games of the Shadowrun setting are a fusion of Cyberpunk and Elfpunk.

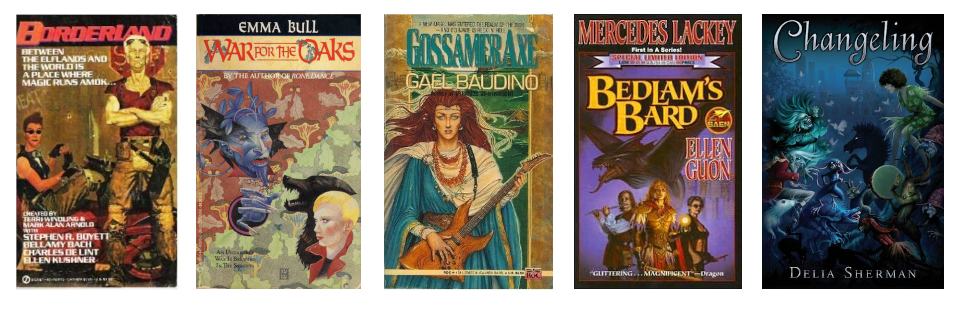

Examples of elfpunk literature include Borderland edited by Terri Windling (1986), War for the Oaks by Emma Bull (1987), Gossamer Axe by Gael Baudino (1990), Bedlam’s Bard by Mercedes Lackey and Ellen Guon (1992), and Changeling by Delia Sherman (2006).

New Punks: A Cautionary Discourse

In addition to those listed above, there is a plethora of other ‘Punk genres out there with new ones popping up all the time, such as sandalpunk, transistorpunk, solarpunk, and even stonepunk. Needless to say, some of these thematic groupings are so niche as to provoke discussions as to whether there’s enough recognized content to codify a new genre. In the past, genres weren’t typically named until years or decades after their inception and were done so by way of professional discourse between authors, editors, and literary scholars. In today’s age of instant gratification and with over a century of established speculative fiction genres behind us, we’re often want to slap a label on a “new genre” as soon as something new appears.

In some cases, the -punk suffix is attached to words to define new subgenres or niche sub-subgenres without specifically fitting into the original punk cultural themes or the literary traditions of exploring the impact of technology on humanity. Others might simply be variations on existing subgenres or be taking up the ‘punk moniker while an existing subgenre of speculative fiction might already exist for them to join. Sandalpunk is a good example of both, as one might have difficulty drawing a clear line between this and classic sword and sandal fiction or even simply sword and sorcery. This leads us to the inevitable problem we often run into with genre studies: not everything fits neatly in labeled boxes and some of the boxes overlap quite a bit.

Just like Blade Runner challenged us to consider what makes us human, I believe studying ‘punk genres should make us ask, “What is punk?”

Special thanks to Stephen Coghlan, whom I interviewed as a source of information on the sub-genres of clockpunk and dreampunk. Stephen is an author of various genres, including several mentioned here! His insight into these genres was invaluable, especially in navigating the turbid depths of dreampunk.

Find out what Stephen is up to on Twitter, and check out his web site HERE.