If you’ve found yourself here, you probably love fantasy literature. One of the most fascinating things about the genre, I think, is where it came from and how it became what it is today. I’m also enthralled by the many fantasy subgenres and the nuances of how they explore the fantastic in different ways.

Navigating fantasy literature and its myriad subgenres can be a daunting task. In this first leg of a multi-part journey, we will discover what the fantasy genre is and explore the history of fantasy literature with notable examples of authors and works that shaped the genre.

What is Fantasy?

Fantasy is a super-genre encapsulating a myriad of subgenres across many mediums of entertainment which contain magical, mythical, and supernatural elements.

The term fantasy originates from the Greek “phantasia”, which essentially describes any sort of imaginary manifestation. Hence, fantasy consists of things that can only be imagined. Some define this further as any form of literature that contains fantastic elements, such as the magic, mystical creatures, the supernatural, and imaginary worlds. A story need not contain all these, and can surely have mundane elements as well, but the presence of any of them gives a tale a sense of the fantastic.

Because of this loose definition, works that can inarguably be considered fantasy might vary so much that they hardly resemble one another. Two recent examples of popular media that illustrate these extremes are the television series Game of Thrones (based on A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin) and Lost. While the former takes place in an entirely fictional world with magic, the undead, and dragons, the latter takes place in our reality but contains supernatural elements. Lost even goes as far to set the expectation that everything has a rational explanation until later in the series.

These massive differences within the genre are why there are so many subgenres of fantasy literature, which we will explore soon!

Fantasy Literature’s Historic Journey

While use of the term “fantasy” to describe a genre of literature came about in the early twentieth century—a recent development on the scale of the historical timeline—its origins reach far into the past. Many tales through history inspired the eventual creation of fantasy literature, and we might retroactively recognize works from as far back as the Renaissance as part of the genre. Over time, the myths, legends, and fairy tales of old evolved and grew to become the multi-faceted super-genre we recognize today.

The Origins of Fantasy

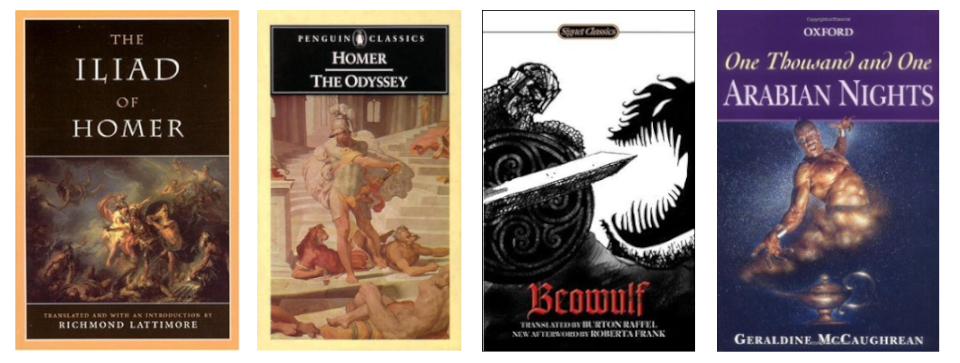

Think of some of the oldest tales told by mankind—epics such as the Iliad and the Odyssey, Beowulf, and The Book of One Thousand and One Nights. All of these stories, originating from diverse cultures, all have something in common: elements of the fantastic. They include things such as deities, monsters, and magic. While these myths and legends were part of the religions and/or cultural identities of their authors, these great works of the past laid the foundation for what would eventually become fantasy literature.

The oldest written work discovered by historians can actually be considered part of this proto-fantasy legacy. The Epic of Gilgamesh was likely passed down verbally for generations, to eventually be written on clay tablets around four-thousand years ago in the region of Mesopotamia, over time by both the Sumerian and Bablylonian peoples.

This epic poem details a heroic quest for immortality by the eponymous King of Uruk, Gilgamesh. On his journeys, he confronts monster and gods. This work is also considered the first heroic epic in history and may have inspired the Greek myths that we see in the works of Homer and others.

Fairy Tales and Words of Wonder

From antiquity through the Middle Ages, religious myths and local legends remained the bedrock of storytelling around the world. New cultures brought new ideas and stories containing elements familiar to any fan of fantasy literature, such as the elves and dwarves of Germanic and Norse mythology. Fairy tales became commonplace, especially in northern Europe, many used to convey moral and practical lessons to children or to simply frighten them from wandering away from home.

In the late medieval period and the Renaissance, the value of storytelling shifted from sharing religious and cultural ideas to the creation of fictional situations for entertainment or artistic value. The invention of the printing press around 1436 facilitated a boom in the availability of printed works of literature. Even in Globe Theatre, Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1600) used fairy tale elements to entertain the people of seventeenth-century London.

Fantasy in the Victorian Era

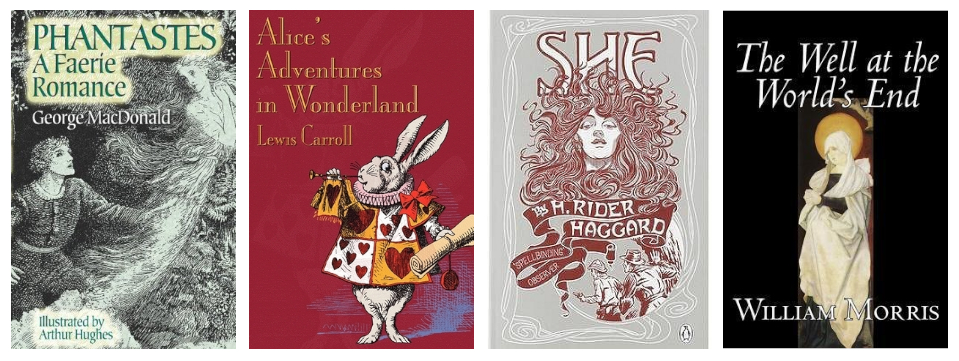

The nineteenth century saw a boom in the number of books being produced thanks to the mechanization of the printing press. During this time, the trend of fiction dominating storytelling over myth surged. The novel became more popular and the number of authors writing them more numerous. Romanticism was the dominant artistic movement of the time, which sought to explore the individual human experience and critique society at large.

Despite all this, the closest there was to fantasy fiction were books of collected fairy tales from the past, a form of folklore intended primarily for an audience of children due to their unique blend of elements of wonder and moral lessons.

This all changed with Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women, written by Scottish author George MacDonald in 1858. This book is considered by many to be the first fantasy novel written for an adult audience. Another notable work of this time is The Well at the World’s End (1869) by William Morris, which many consider to be the prototype for high fantasy due to its entirely fictional setting. Other ventures into the fantastic during this time include Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll and She: A History of Adventure (1887) by H. Rider Haggard.

The Golden Age of Fantasy

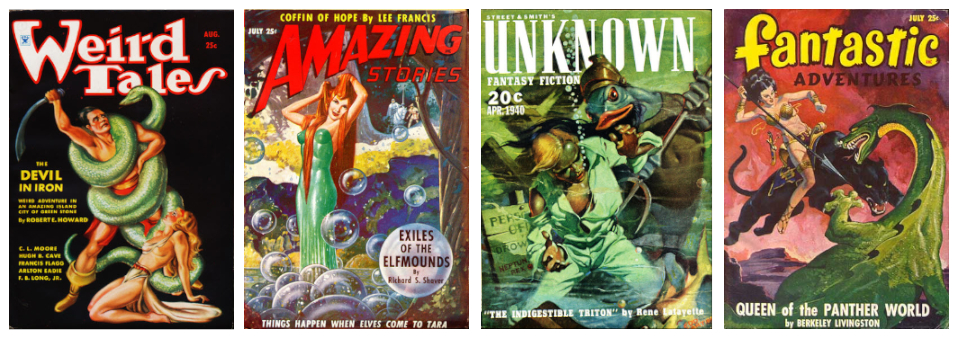

The journey from fringe explorations of the fantastic to dominating popular culture began in the first half of the twentieth century in pulp fiction magazines. Weird Tales launched in 1923, focusing on fantasy and horror, although the term “weird fiction” was still being used at the time as a bit of a catchall term for these types of stories. Many other magazines printed a variety of genre fiction or focused on fantastic stories during this time, such as Amazing Stories, Unknown, and Fantastic Adventures.

Special thanks to Galactic Central for their amazing pulp fiction cover archive.

Due to the economic upheaval and the shadows of great wars in the first half of the century, many people turned to the pulps for escapism entertainment, leading to a boom in the industry. From the 1920s to the late 1940s, hundreds of titles could be found on newsstands across America and the United Kingdom. In 1949, Mercury Press published the first issue of The Magazine of Fantasy, which was the first use of the term “fantasy” to define the genre. (The title of the publication changed to The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction starting with the second issue.)

Many authors gained popularity writing stories for the pulp magazines. Two of the pillars of the movement were Robert E. Howard, author of the Conan the Barbarian stories, and Fritz Leiber, who introduced Fahfrd and the Gray Mouser in 1939’s “Two Sought Adventure”, published in Unknown. They each are respectively considered the founding fathers of the sub-genres of Heroic Fantasy and Sword and Sorcery.

In 1937, J.R.R. Tolkien published The Hobbit. This book is considered by many to be the birth of the high fantasy subgenre—involving entirely fictional worlds—which dominated the rise of the fantasy genre in the later twentieth century.

This book introduced us to an entire world of fantasy, which Tolkien dubbed Middle-Earth. Elements such as wizards, elves, and dwarves drew inspiration from the folklore and fairy tales of Tolkien’s native England, which had Celtic roots but were influenced by Germanic and Norse mythology due to immigration to the British Isles after the fall of Rome.

Tolkien again broke ground when he published The Fellowship of the Ring in 1954. Following up on the widely popular The Hobbit, this and the subsequent volumes in The Lord of the Rings trilogy would go on to establish the sub-genre of epic fantasy. Many fantasy stories before this focused personal conflict, encounters with the mystical, or journeys into magical realms, but The Lord of the Rings trilogy upped the stakes to a struggle for the fate of the world itself.

Also notably, these books gained respect for the genre of fantasy with the literati of the time, who had previously viewed it with quite a bit of disdain thanks to the legacy of pulp fiction magazines churning out massive amounts of content of variable quality.

As Tolkien was exploring Middle-Earth, a good friend of his found another fantasy realm to explore. In 1950, C.S. Lewis published The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the first book of what would become The Chronicles of Narnia. Lewis stayed closer to the traditions of fairy tale stories with his venture, but like Tolkien, he broke new ground by mixing elements from various traditions instead of focusing on a singular element of folklore or writing magical medievalism.

However, while Tolkien painstakingly crafted an entirely fictional world for his fantasy stories, Lewis opted to send the Pevensie children through a gateway to another world existing alongside our own. This difference would set the foundation for the two broadest subgenres of fantasy literature: high fantasy and low fantasy—the latter of which involves fantastic elements in our world or travel from our world to a fantasy realm.

It should be noted that there is room for debate on this last point. Some consider Lewis’ work to be high fantasy because most of the story takes place in Narnia. This links to the question of whether portal fantasy counts as low fantasy or high fantasy, or if it should be another category independent of the two. I lean toward the camp that if Earth is involved, it’s low fantasy, since high fantasy is defined as being a secondary world detached from our own. I discuss this further in The Fantasy Divide.

On the Shoulders of Giants

Despite the decline of the pulps due to the rise of television and other factors, fantasy fiction remained popular in the post-war period, although it was less mainstream and became more of a niche than the norm in the publishing industry. However, the creative momentum of the genre and a loyal audience persisted through the 1960s and 1970s. Notable publications from these decades include A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) by Ursula K. Le Guin, Dragonflight (1968) by Anne McCaffrey, The Sword of Shannara (1977) by Terry Brooks, and The Neverending Story (1979) by Michael Ende.

The genre gained a new following with young people in the late 1970s and grew in popularity once more over the next twenty years. This was in no small part thanks to the popularity of the Dungeons & Dragons role playing game created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson in 1974 and the associated tidal wave of books set in several fantasy worlds published by TSR over the next twenty-five years. This was the time that I became a fan of fantasy literature, and some of my favorite books of the era include Dragons of Autumn Twilight (1984) by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman, The Crystal Shard (1988) by R.A. Salvatore, The Verdant Passage (1991) by Troy Denning, and I, Strahd: The Memoirs of a Vampire (1993) by P.N. Elrod.

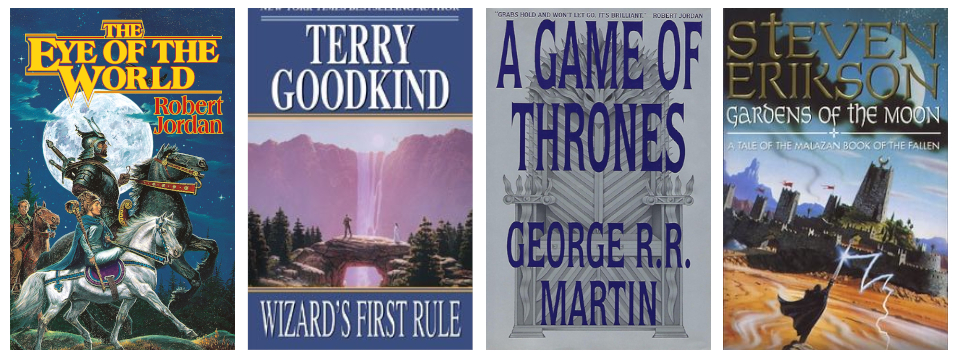

All of this brings us to what some consider the golden age of epic fantasy. In the 1990s, multi-volume-spanning epic series were published. Notable among these are Terry Goodkind’s The Sword of Truth (begun with Wizard’s First Rule in 1994), George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire (begun with A Game of Thrones in 1996), and Steven Erickson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen (begun with Gardens of the Moon in 1999). Although these series began publication in the 1990s, all of them continued to release volumes well into the twenty-first century. The Wheel of Time series—considered by many to be the magnum opus of epic fantasy—even outlived its creator, the late Robert Jordan. Begun in 1990 with The Eye of the World, the series was completed by Brandon Sanderson with the publication of A Memory of Light in 2013.

Modern Fantasy Literature

Of course, other authors have taken up the pen, or keyboard, in the twenty-first century to continue this great tradition of fantastic storytelling. Existing subgenres like epic fantasy have continued to gain in popularity, while a myriad of others such as urban fantasy, dark fantasy, and fantasy romance have exploded onto bookshelves in the last two decades.

The landscape of modern fantasy is also a more diverse one. Once dominated by white men in the United States and United Kingdom, fantasy literature is now seeing a surge in authors of all gender, sexuality, ethnic, racial, national, social, and cultural backgrounds. Some exciting works breaking into the genre from authors of varied demographics include The Fifth Season (2015) by N.K. Jemisin, The Grace of Kings (2015) by Ken Liu, The Poppy War (2018) by R.F. Kuang, and Children of Blood and Bone (2018) by Tomi Adeyemi.

Fantasy Storytelling on the Screen

While writing and publishing a book is a daunting proposition, producing a film or television series is a much more expensive and complicated one. Because of this, film and television must reach a wider audience to be considered successful. When we see our favorite speculative genres hit the screen, that is a sign that they are gaining a more mainstream appeal.

Early in the twenty-first century, film adaptations of popular fantasy literature took the world by storm, introducing new audiences to the wonders of these magical stories. Notable film adaptations that flooded theaters include The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (2001), The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (2005), and Twilight (2008).

The box office success of these films likely also paved the way for fantasy television series based on books such as True Blood (2008), Game of Thrones (2011), The Magicians (2015), and Shadow and Bone (2021), greatly expanding the breadth of fantasy entertainment available and treating these meaty stories with the breathing room offered by this long-form visual storytelling format.

Fantastic Legacies

As we can see, the fantasy genre can trace its roots far back to the early days of verbal storytelling and poetic epics such as Homer’s The Odyssey, but did not rise to widespread popularity until the efforts of pulp writers such as Robert E. Howard and Fritz Leiber in the early twentieth century. The groundbreaking achievements of Tolkien, Lewis, McCaffrey, and Jordan helped the genre to grow and mature, film and television brought fantasy storytelling to new audiences, and now intrepid newcomers such as Jemisin, Liu, Kuang, and Adeyemi are taking the helm and—like Odysseus—are steering fantasy literature into uncharted waters.

On the next leg of our journey, The Fantasy Divide: Low vs High Fantasy, we will explore the two sides of the fantasy literature coin, how they came to be, and prominent features of each.

The Complete Guide to Fantasy Literature

- The History of Fantasy Literature

- The Fantasy Divide: Low vs High Fantasy

- High Fantasy and its Major Subgenres

- Low Fantasy and its Major Subgenres

- More Subgenres of Fantasy Literature