One of the fascinating things about fantasy literature is how many different types of stories fall under this massive umbrella genre. Everything from elves and goblins in a medieval setting to witches and vampires in the modern day can be considered fantasy. This has led to a plethora of subgenres that help us communicate and identify what kind of fantasy a story is. The number of these is growing all the time, so it’s hard to even count them all. In this essay, we’ll take a closer look at some of the most enduring, popular, and interesting of these.

While subgenres of fantasy literature don’t all fall neatly into a hierarchy, there are generally two major ways to identify them: either by the elements they possess or by the time period they are inspired by or set within. We’ll start by exploring some subgenres defined by their elements, then we’ll take a look at a few subgenres which deviate from the norms of medieval and contemporary fantasy.

If you’ve come to this page without reading the other essays in this series, you might be wondering, “Where is epic fantasy? What about intrusion fantasy?” Those and more are already covered in the essays on high fantasy and low fantasy and their major subgenres.

Fantasy Subgenres Defined by Elements

Many subgenres of fantasy literature can be identified by their elements, such as the tone they use to set a mood, specific tropes they include, or a general sense of style comprised of more esoteric factors. When you pick up a fantasy book and are immediately thrust into the mud, blood, and horrors of war, you might be looking at military fantasy. If it’s set in a modern city with a focus on romance, particularly with someone who is not quite human, it could be paranormal romance. For this section, we’ll explore the subgenres alphabetically.

While the term “trope” can have a pejorative connotation, it is important to remember that a trope is simply a common element found across a genre. Tropes are therefore the building blocks of genre fiction—fantasy literature wouldn’t be recognizable without them. However, using tropes without mixing them up or telling a story in a new way can lead to a repetitive formula that becomes a cliché.

Anthropomorphic Fantasy

Anthropomorphic fantasy, sometimes unofficially called furry fantasy, consists of fantasy stories that feature anthropomorphized creatures—animals that have been given human-like attributes. These creatures can behave like regular animals with the addition of rational thought and the ability to speak or might walk upright, wear clothing, and interact with tools and weapons. The range of tone, theme, and plot structures in these books can vary wildly. Some are lighthearted and funny while others can be dark and serious. While many fantasy worlds include anthropomorphized species alongside humans, elves, and so on, in this subgenre, they are the main focus of the story or even the sole society of the world.

A few great examples of anthropomorphic fantasy include The Wind in the Willows (1908) by Kenneth Grahame, Watership Down (1972) by Richard Adams, and Redwall (1986) by Brian Jaques. The latter is one of my favorite books and was the beginning of a series of twenty-two novels and a handful of spinoffs, including a cookbook.

Bangsian Fantasy

Named for American author John Kendrick Bangs, Bangsian fantasy stories deal with the afterlife, often set in these supernatural realms with the spirits of the deceased acting as the main characters. Bangs’ own stories often featured figures from both history and mythology, focusing on exploring how these characters might interact by showing them in conversation. This plot-light type of story is typical of the genre, as is a bit of satire, but an author could definitely set the characters against a more substantial conflict. Naturally, some of these stories deal with very deep themes of morality, theology, life, death, and the afterlife.

The first book Bangs wrote in this manner, which established the genre, was A House-Boat on the Styx (1895). Other examples of the genre include What Dreams May Come (1978) by Richard Matheson and Damned (2011) by Chuck Palahniuk.

Cozy Fantasy

If your favorite parts of The Hobbit or The Fellowship of the Ring are the opening chapters set in The Shire, which focus on the lives of the hobbits, cozy fantasy is a genre you may want to explore. Cozy fantasy books generally take place in a pleasant setting like a small village or a roadside inn, although a more urban setting and travel are not uncommon in the genre. The narratives to be found vary, including stories focusing on a romance or a mystery, but slice-of-life stories are very common. Conflicts are normally of a more personal nature or encompass a limited scale, though not as a rule. Life and death stakes might occur, but violence is kept to a minimum or completely eschewed. Likewise, you won’t normally find anything on the spicy end of romance here. This recently emerging genre has gained a lot of popularity in the last five years, likely because many of us are exhausted by contemporary reality and just want to read a book that feels like being wrapped up in a fuzzy blanket with a hot cup of tea.

Examples of cozy fantasy include A Wizard’s Guide to Defensive Baking (2020) by T. Kingfisher, The House in the Cerulean Sea (2020) by T.J. Clune, Can’t Spell Treason Without Tea (2022) by Rebecca Thorne, Legends & Lattes (2022) by Travis Baldree, and Emily Wilde’s Encyclopaedia of Faeries (2023) by Heather Fawcett.

Dark Fantasy

One of my favorite subgenres of fantasy literature, dark fantasy incorporates elements of horror literature into a fantasy story. These tales might evoke the days of gothic fiction, paying homage to a time before the emergence of modern fantasy and horror, or it can take inspiration from contemporary horror fiction to put a dark twist on a fantasy world. These inspirations can emerge in the form of vampires, demons, mad scientists, necromancers, and a slew of other nefarious villains and concepts. The key element here is that there should be a definite tone of dread, tension, and fear. We often see dark fantasy applied to high fantasy stories, but it can coincide with contemporary or historical fantasy. However, those blur the line between this subgenre and being actual horror literature, gothic fiction, or weird fiction. There is definitely a gray area and quite a bit of overlap between all these genres.

Some chilling examples of dark fantasy include The Gunslinger (1982) by Stephen King, Black Sun Rising (1991) by C.S. Friedman, I, Strahd: The Memoirs of a Vampire (1993) by P.N. Elrod, Daughter of the Blood (1998) by Anne Bishop, Kingdom of Ashes (2016) by Elena May

Grimdark Fantasy

Grimdark fantasy is exactly what it sounds like: it is grim, and it is dark. It is not to be confused with dark fantasy, which incorporates elements of horror fiction, although the two can be combined. Stories in this genre are often set in dystopian settings and focus on the grim realities of life, death, and war. They deal with gray areas of morality and do not shy away from graphic violence. Grimdark fantasy is applauded by some for offering a more realistic take on the fantasy genre. There are often character-driven stories with flawed protagonists that are easy to relate to, and some stories explore complicated political situations which do not have a clear good-versus-evil resolution.

Some examples of grimdark fantasy include A Game of Thrones (1996) by George R.R. Martin, The Blade Itself (2006) by Joe Abercrombie, Prince of Thorns (2011) by Mark Lawrence, The Grim Company (2013) by Luke Scull, and The Court of Broken Knives (2017) by Anna Smith Spark.

Military Fantasy

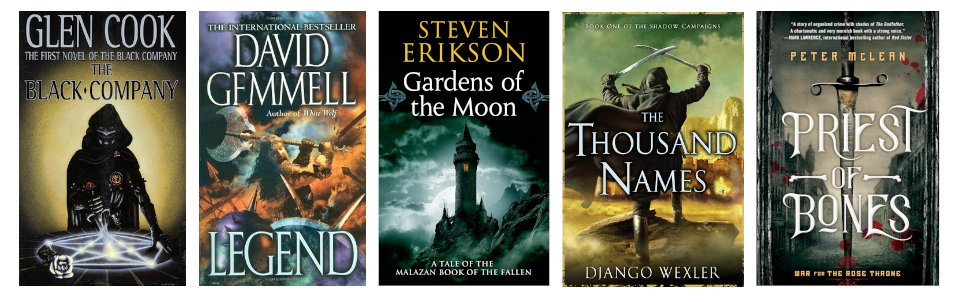

While a lot of fantasy stories involve armies, especially in epic fantasy, the people who make up those armies are usually nameless and faceless. Military fantasy is often also epic fantasy, but instead of focusing on larger-than-life heroes on a grand quest, it gets its boots in the mud with the soldiers just doing their job and trying to survive. The most important characters in these books are part of the military machine. They might hold special roles, such as scouts or battlemages, or they could be part of the ordinary rank and file. These stories explore the horrors of war or the psychological wounds that linger long after one has left service.

Some great entry points into military fantasy include The Black Company (1984) by Glen Cook, Legend (1984) by David Gemmell, Gardens of the Moon (1999) by Steven Erikson, The Thousand Names (2013) by Django Wexler, and Priest of Bones (2018) by Peter McLean.

Mythological Fantasy

Mythological fantasy, or mythic fiction, involves stories which include elements from real-world mythologies. These might be set contemporary to the mythology—such as a story in ancient Greece with elements of Greek mythology—or in modern times. How this subgenre presents these elements ranges from staying true to the source material to drawing inspiration from it but presenting these concepts in an entirely new light.

Notable examples of mythological fantasy include Good Omens (1990) by Terry Pratchett & Neil Gaiman, American Gods (2001) by Neil Gaiman, The Lighting Thief (2005) by Rick Riordan, Hounded (2011) by Kevin Hearne, and Circe (2018) by Madeline Miller.

Mythopoeia

Similar to mythological fantasy, mythopoeia or mythopoesis (literally: “myth making”) is fantasy with a focus on mythological elements, but in these books, the mythology is entirely fictional. Anybody who has delved into a bit of worldbuilding may have dabbled in mythopoesis, but authors of this genre focus on the mythos they have created. A seminal example of this is The Silmarillion (1977) by J.R.R. Tolkien.

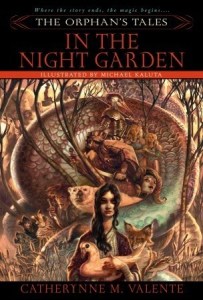

Mythpunk

Completing the mythological triumvirate, mythpunk draws on mythological elements, breaks them down, and gives them a post-modern twist. It uses elements of mythology, folklore, and fairy tales, but dissects them and reassembles them in new ways using post-modern literary experimentation such as non-linear storytelling, unreliable narrators, and intertextuality. The term was coined by Catherine M. Valente, so her book The Orphan’s Tales: In the Night Garden (2006) stands out as a prominent example of the subgenre.

Romantic Fantasy & Fantasy Romance

While some books borrow elements from fantasy for romance fiction, others are rooted in fantasy and borrow elements from romance. This can be approached in many ways, and a lot of fantasy books have at least a touch of romance, but romantic fantasy and fantasy romance lean heavily into the romantic side of things.

Romantic Fantasy

Romantic fantasy, also called romantasy, is fantasy with romance. The main story is a fantasy one, be that an epic quest or some other fantastic adventure, but a romantic subplot plays a major role. However, were you to take out the romance, you’d still have a fantasy story. Examples of this subgenre include Wild Magic (1992) by Tamora Pierce, The Charmed Sphere (2004) by Catherine Asaro, and The Fairy Godmother (2004) by Mercedes Lackey.

Fantasy Romance

Fantasy romance, on the other hand, is romance with fantasy. The romance is the main plot, and everything else is there to support it. If you were to take the romance out of one of these stories, the narrative would fall apart. Some notable works in this subgenre are The Princess Bride (1973) by William Goldman, A Court of Thorns and Roses (2015) by Sarah J. Maas, and The Awakening (2020) by Nora Roberts.

Urban Fantasy

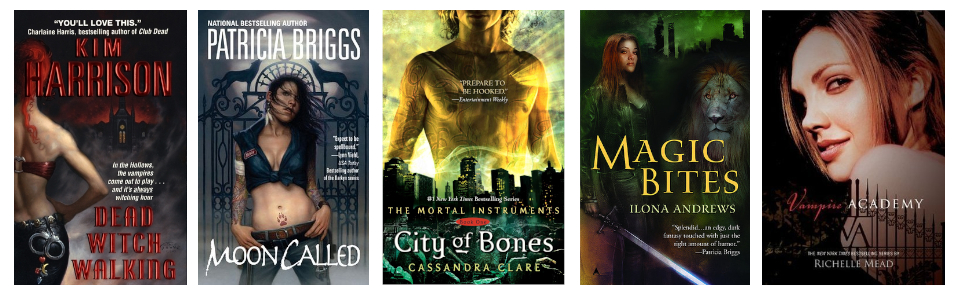

Urban fantasy is a subgenre of contemporary fantasy characterized by taking place in an urban or suburban setting in the recent past, present, or near future relative to when it is written. This might be a large city such as Chicago or London, the suburbs of a major metropolitan area, a smaller city, or even a moderate-sized town. The key distinction of the subgenre is less about population density in more that the setting acts almost like another character in the story. Rather than being a backdrop, it informs the shape of the story and the worldview of the characters. The fantastic elements may be a regular part of life, but most often they exist in secret on the fringes of society or may be invasive elements, crossing over with intrusion fantasy. Though these stories may be written for any age range, the most common target for urban fantasy is the young adult audience, particularly young women. As such, the protagonists in urban fantasy are often young women. Common themes of urban fantasy include conflict between the mundane and the fantastic and/or changes a protagonist undergoes after exposure to previously concealed fantastic elements.

Popular examples of urban fantasy include Dead Witch Walking (2004) by Kim Harrison, Moon Called (2006) by Patricia Briggs, City of Bones (2007) by Cassandra Clare, Magic Bites (2007) by Ilona Andrews, and Vampire Academy (2007) by Richelle Mead.

Paranormal Romance

Paranormal romance shares a lot in common with urban fantasy, in that it takes place in a contemporary, usually urban or suburban setting with fantastic elements. While almost all paranormal romance is also urban fantasy, the converse is not always the case. While urban fantasy can feature a romantic subplot, if the main focus of the story is the romance, then it is probably paranormal romance. You’ll often see fantastic characters such as vampires, werewolves, fae, or magic users as the love interest for a mundane protagonist. Like urban fantasy, paranormal romance often deals with how the protagonist’s life is altered by exposure to the fantastic, but this change is driven by or drives the romance. This genre also targets young adult women in most cases.

Examples of this genre include Dead Until Dark (2001) by Charlaine Harris, Twilight (2005) by Stephanie Meyer, Dark Lover (2005) by J.R. Ward, Halfway to the Grave (2007) by Jeaniene Frost, and Beautiful Creatures (2009) by Kami Garcia and Margaret Stohl.

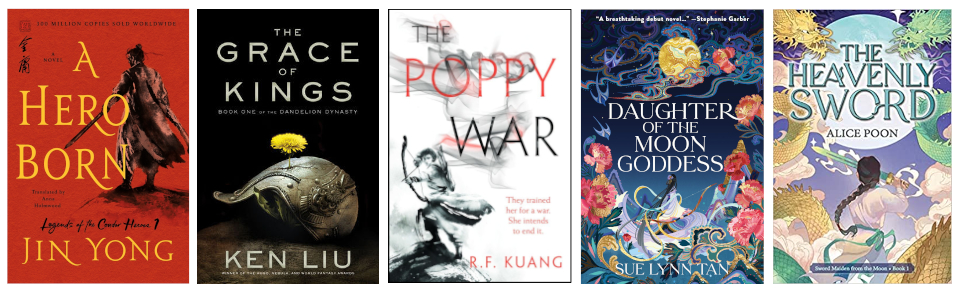

Wuxia and Xianxia

China—covering almost the same landmass as all of Europe—has a long, rich history and engrossing traditions of myth and folklore all its own. Stories based on these traditions are nothing new, but in western fantasy publishing, they have recently become more present and increasingly popular. While some books in these genres are grounded in the history and folklore of China, others might draw inspiration from these and set entirely new events in a secondary world.

A core element of both wuxia and xianxia is the concept of xiá (俠), which translates as hero, chivalrous, or vigilante. Xiá is a martial code of conduct similar to European chivalry or Japanese bushido. Followers of the code of xiá extoll the virtues of righteousness, honor, and in some cases, vengeance upon those who have wronged the defenseless. Hence, a xiá hero is reminiscent to the folk heroes of European traditions, such as Robin Hood.

Wuxia

Wuxia (武俠) combines the above xiá with wǔ (武), meaning martial, military, or armed. Thus, wuxia is a genre of “martial heroes” inspired by Chinese history and focused on the martial arts. Traditional wuxia is mostly historical fiction which toes the line with alternative history and historical fantasy, but some modern authors dive deeper into the fantastic and may even set their stories in secondary worlds. Some prominent examples of wuxia fantasy include A Hero Born (1957) by Jin Yong, The Grace of Kings (2015) by Ken Liu, and The Poppy War (2018) by R.F. Kuang.

Xianxia

Xianxia (仙俠), similar to wuxia, combines our folk hero with another concept. This time, the theme switches to xiān (仙), which are entities from Chinese mythology such as powerful spirits or someone who has transcended mortality. This then is a genre of “immortal heroes” inspired by Chinese mythology and focused on mythological figures. Again, much of this genre takes place in a historical setting, but some authors delve into secondary worlds inspired by Chinese history and mythology. Two great examples of this genre are Daughter of the Moon Goddess (2022) by Sue Lynn Tan and The Heavenly Sword (2023) by Alice Poon.

Fantasy Subgenres Defined by Time Period

When it comes to high fantasy and historical fantasy, almost all stories written in the twentieth century were inspired by or set in medieval Europe. Even in the last twenty years, this remains a predominant trend, although exploring other periods has become more popular. Because of this, fantasy literature that is inspired by or set in other periods is usually given further subgenre labels to distinguish it from the mainstream of medieval fantasy.

Keep in mind that these subgenres only refer to time period, so stories that carry them will also fit into other genres that better describe their substance, such as a bronze age fantasy with horror elements being both sword & sandal and dark fantasy. In this section, we’ll explore these subgenres chronologically.

Sword & Sandal Fantasy

Sword & sandal fantasy, sometimes called sandalpunk, covers fantasy stories inspired by or set in ancient times. These inspirations and settings range from the dawn of civilization and metalworking to the fall of the western Roman Empire. Cultural elements from ancient Egypt, Greece, or Rome can be prominent, or a story might venture away from the Mediterranean. Mythological fantasy is a clear pairing for this period, and it often goes hand-in-hand with sword & sorcery tales.

In fact, some of the earliest examples of both sword & sandal and sword & sorcery, and still among the most popular, are stories about Conan the Cimmerian and Kull of Atlantis by Robert E Howard, first appearing in pulp fiction magazines in the 1920s-30s. Great introductions to Howard’s contributions to the genre are The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian (2002) and Kull: Exile of Atlantis (2006).

It should be noted that “sword & sandal” can also refer to historical fiction in an ancient setting.

Flintlock Fantasy

When it comes to high fantasy and historical fantasy, one normally expects to see sword-swinging heroes. However, there are also great tales to be told in settings that have adopted the use of firearms. Flintlock fantasy settings are still pre-industrial, but in a time where gunpowder weapons are commonplace. These stories take place during or are inspired by the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. The age of sail, the Napoleonic Wars, and revolutions such as the American Revolution are all common inspirations for these tales. Because the wars and revolutions of the era are such a significant influence on the genre, a substantial proportion of flintlock fantasy books are also military fantasy and quite a few are historical fantasy, but these are far from being rules.

Some wonderful examples of flintlock fantasy include His Majesty’s Dragon (2006) by Naomi Novik, At the Queen’s Command (2010) by Michael A. Stackpole, Promise of Blood (2013) by Brian McClellan, The Thousand Names (2013) by Django Wexler, Guns of the Dawn (2015) by Adrian Tchaikovsky.

Gaslamp Fantasy

A cousin to steampunk, gaslamp fantasy shares that genre’s Victorian- or Edwardian-era setting but adds a twist of the fantastic. These tales are set from during the height of the industrial revolution to just before the modern era, roughly 1830 – 1910, or in a secondary world inspired by this time. Many of these stories keep the technology of the setting mundane and focus on adding supernatural or magical elements, but in some cases may include anachronistic technology like airships and steam-powered automatons, with the shared time period creating a comfortable overlap between steampunk and gaslamp fantasy.

Great examples of gaslamp fantasy include Northern Lights (1995) by Philip Pullman, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell (2004) by Susanna Clarke, The Alloy of Law (2011) by Brandon Sanderson, The Night Circus (2011) by Erin Morgenstern, and The Goblin Emperor (2014) by Katherine Addison.

Diverse Worlds to Explore

As you can tell from this tour of subgenres, the diversity of fantasy literature is as boundless as the limits of our imaginations. Hopefully you found something new here that piques your interest or discovered that something you already love has a name so you can find more of its kind. Or, if you’re a writer, maybe found some inspiration for a future project. I think a key thing to remember from all of this is that not every book fits neatly on one shelf. Many of the greatest books out there blend elements from several subgenres in innovative ways to tell entirely new kinds of stories.

While you’ve reached the end of our tour of fantasy literature, I hope your exploration of these amazing worlds will continue for years to come. If you want to learn about other genres of speculative fiction, return to the Genre Studies page to discover more!

The Complete Guide to Fantasy Literature

- The History of Fantasy Literature

- The Fantasy Divide: Low vs High Fantasy

- High Fantasy and its Major Subgenres

- Low Fantasy and its Major Subgenres

- More Subgenres of Fantasy Literature