When exploring fantasy literature, there is a clear line that can be drawn down the middle of the genre. On one hand, some fantasy stories take us on journeys contained within fantastic worlds. On the other, fantastic elements encroach on our reality or we travel from the real world to a fictional one.

I feel that at the very top of the hierarchy of fantasy subgenres lie high fantasy and low fantasy. Unlike other subgenres, which authors routinely mix and match to brew up their own unique magical potions, these categories exist as two sides of a coin, and that coin encompasses all of fantasy literature.

Definitions of Low Fantasy and High Fantasy

Before we dive into how these subgenres came to be, it is good to have a rough understanding of what they are and the differences between them. I will go into more detail on each in this series’ essays on High Fantasy and Low Fantasy, but for now, a brief explanation of the differences will do.

It is worth noting that there are a lot of interpretations of genre conventions, and not all of them are in perfect alignment. Studying art of any kind leaves some room for subjectivity, so you’re going to see different takes on defining things as you explore them further.

That being said, most sources will agree that high fantasy takes place in a fictional setting independent of our reality. There is little-to-no debate on this. Where things get tricky is with low fantasy, and particularly the question of portal fantasy. Some sources say low fantasy takes place entirely on Earth—hard stop. Others say low fantasy takes place either entirely in our reality or between our reality and a fictional setting, such as with residents of Earth travelling to another realm in portal fantasy.

I prefer the latter interpretation because it agrees with the definition of high fantasy. If high fantasy must be a story set in a fantasy world independent of our own, it stands to reason that if one can travel from our world to a fantasy world within a story, that is low fantasy.

Hence, I would explain the difference as such: High fantasy is set in an entirely fictional reality, while low fantasy is set either entirely in our reality or with a connection between our reality and a fictional one.

Prototypes of Low Fantasy and High Fantasy

While the concepts of low and high fantasy are a wholly twentieth-century invention, the legacy of these genres can be drawn further back in time. Of course, they both can trace their lineages all the way back to The Epic of Gilgamesh, but their direct ancestors—the ones that set the example for these two monumentally different approaches to fantasy literature—came about during the Victorian era.

Low Fantasy’s Prototype

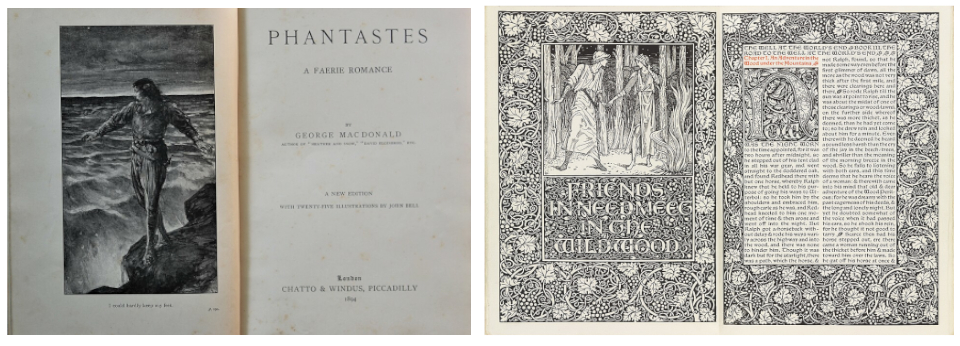

As mentioned in our history of fantasy literature, Scottish author George MacDonald was the first to break away from childrens’ fables and fairy tales in 1858 with his novel Phantastes: A Faerie Romance. While still arguably a fairy tale, it was a tale for adults, and is considered by most to be the first fantasy novel. Telling the story of a young man native to Earth who is drawn into a fantastic realm, this book was also the prototype for low fantasy.

High Fantasy’s Prototype

Possibly the first book to truly leave our world behind and explore a realm entirely of the imagination was The Well at the World’s End by English author William Morris, published in 1896. This tale of adventure, magic, and romance—inspired by fairy tales but diverging from setting them in our world—follows the quest of a young knight seeking the titular well that is fabled to grant everlasting life. It is set in a fictional medieval kingdom with no mention of anywhere on Earth, making it likely to be the first example of a secondary world setting, the defining feature of high fantasy.

Right: The Well at the World’s End by William Morris, pages 286-287, illustrated by Edward Burne-Jones (1896)

Establishing Low Fantasy and High Fantasy

Despite the early forays into other realms by both MacDonald and Morris, most fantasy stories over the next several decades either followed the formula of folklore and fairy tales that preceded these works or took inspiration from them to spin magical twists on historical fiction. That was all changed by an unexpected journey.

There and Back Again

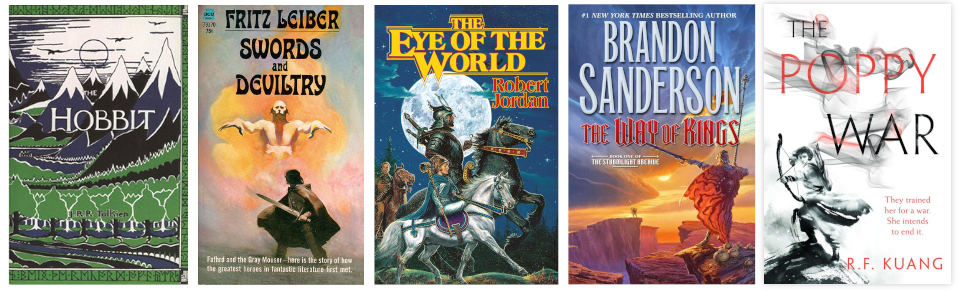

Most agree that the first book to codify the genre of high fantasy was The Hobbit, or There and Back Again by J.R.R. Tolkien, published in England in 1937. While Tolkien himself stated he intended the story to fill a gap in English folklore compared to the long history of stories across the rest of Europe, most accept that the setting of the book, Middle-Earth, is an entirely separate reality from our own. Also, unlike the small scope of The Well at the World’s End, The Hobbit gave us a glimpse into an entire world filled with magical creatures and detailed cultures, pushing the boundaries of what feats of creation we might accomplish with the human imagination.

Through the Wardrobe

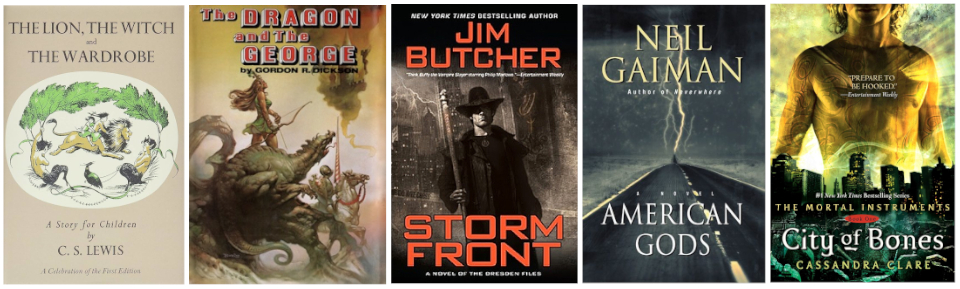

While Tolkien continued to explore Middle-Earth in The Lord of the Rings trilogy, his fellow Englishman and long-time friend C.S. Lewis was exploring a world of his own. However, he chose to get there in a completely different way. In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, published in 1950, the protagonists weren’t native to the fantasy world of Narnia that Lewis created. Rather, Lewis followed in the footsteps of George MacDonald. His protagonists were residents of London who fled to the countryside during The Blitz of World War Two, and who later stumbled across a magic wardrobe that transported them to a realm of fantasy. While the world of Narnia is an entire fictional world, it is intrinsically linked to our own Earth. One can consider this the birth of modern low fantasy if one accepts portal fantasy into the club.

Legacies of Low Fantasy and High Fantasy

I think The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and The Hobbit wonderfully illustrate the differences between low and high fantasy. While there is room for debate on this, the different approaches to fantasy worldbuilding connected to or separate from our reality is undeniable. Again, we can interpret low fantasy as occurring either on Earth or a fantasy setting somehow connected to Earth, while high fantasy involves a setting and characters completely independent of our reality. Because of these broad definitions, we could categorize all fantasy stories as either low or high fantasy, making these subgenres the top-tier of the hierarchy of fantasy subgenres—two sides of the fantasy coin.

Right: The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012, Warner Bros/New Line Cinema)

Common Features of Low Fantasy

Because low fantasy can take place in our world or in another with characters from our world, or both, there is a lot of variety to the genre. Some stories take place in a historical or contemporary setting with the added twist of fantastic elements which are part of reality. These types of tales explore what life might be like if magic, the supernatural, or monsters were present on Earth. This can range from hidden forces such as a secretive coven of vampires to elements of everyday life like magic coexisting with technology.

In other cases, we might see a more mundane representation of our reality affected by some sort of magical incursion. These stories often show characters reacting to the sudden revelation that fantastic things are real or a protagonist who is in-the-know dealing with supernatural threats. On the flip side of that, characters from our world might travel to a fantastic realm. These stories often resemble high fantasy, but the fantasy world is entirely alien to the protagonist(s).

Examples of Low Fantasy

Of course, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950) by C.S. Lewis can be considered the most prominent example of low fantasy both for being the first to codify this genre and for its enduring popularity. Other great examples include The Dragon and the George (1976) by Gordon R. Dickson, Storm Front (2000) by Jim Butcher, American Gods (2001) by Neil Gaiman, and City of Bones (2007) by Cassandra Clare.

Common Features of High Fantasy

Taking place entirely in a secondary world—a setting completely independent of our reality—high fantasy plunges us headfirst into the fantastic. These settings are often modeled after medieval Europe, although the growing diversity of modern fantasy authors and overall cultural awareness has led to many stories inspired by other times, places, and peoples. In some cases, the fantasy world might be so unfamiliar that it can hardly be said to resemble any historical era or location.

High fantasy often takes us on some sort of grand adventure and deals with struggles of good versus evil. However, this is a trend rather than a rule. Stories in this genre can range from small-scale, personal narratives to continent-spanning epics with hundreds of named characters. Likewise, just how magical these worlds are can range from these elements consisting of hints and whispers to being part of everyday life. Also, the people, flora, and fauna of a high fantasy world might resemble those found on Earth, be completely alien to us, or anywhere in-between.

Examples of High Fantasy

Again, I’d argue that the best example of a genre is the first one, and in this case that is The Hobbit (1937) by J.R.R. Tolkien. Other wonderful examples of high fantasy include Swords and Deviltry (1970) by Fritz Leiber, The Eye of the World (1990) by Robert Jordan, The Way of Kings (2010) by Brandon Sanderson, and The Poppy War (2018) by R.F. Kuang.

Any Way You Get There

The amazing thing about fantasy literature is that it is limited only by the bounds of imagination, hence it is limitless. Subgenres shouldn’t be seen as restricting the fantastic; when you’re looking for your next great read or setting out to write your own journey, don’t view these differences as limitations. Rather, simply read or write what you love. Then, whatever you discover that to be, genre labels will help you find another book you love or a reader who loves your book. Whether you travel through a portal to another world, face monsters in a darkened alley in Chicago, or set out from an idyllic farm on a grand quest to defeat the dark lord, the important thing is that you enjoy the adventure.

In part three of our journey through fantasy literature, High Fantasy and its Major Subgenres, we’ll take a deeper dive into the realms of high fantasy and explore the subgenres of epic fantasy, heroic fantasy, and sword & sorcery.

The Complete Guide to Fantasy Literature

- The History of Fantasy Literature

- The Fantasy Divide: Low vs High Fantasy

- High Fantasy and its Major Subgenres

- Low Fantasy and its Major Subgenres

- More Subgenres of Fantasy Literature