Exploring all that is encompassed by the name science fiction can be a daunting proposition. Like daring explorers setting out to discover uncharted worlds, this essay takes the first steps into the beyond by first delving into the past. After all, they say you can’t know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been.

- Defining Science Fiction

- Science Fiction of the Past: The Prehistory of the Future

- The Birth of Modern Science Fiction: Literary Realism and the Industrial Revolution

- Pulp Science Fiction: From Amazing to Wonder

- Modern Science Fiction: From Post-War to Post-Modernism

- The Future of Science Fiction: Today’s Tomorrow

Defining Science Fiction

Like any good scientist setting out to examine a subject, we must first codify what we seek. Defining science fiction can seem deceptively simple, but there are so many layers and possibilities that a short definition hardly seems to do this massive genre justice. In the most basic sense, science fiction is literature that speculates on the future or on how scientifically plausible imaginative elements might alter our present. As we are standing upon the shoulders of giants, however, we will allow one of them to lend his own words to this task:

Science fiction can be defined as that branch of literature which deals with the reaction of human beings to changes in science and technology.

Isaac Asimov

At its core, science fiction wonders what our future might be like. Because this is such an open-ended topic, there are a myriad of ways to approach it. Some stories might only peer a few years ahead, positing the ramifications of real-life concerns like climate change or the social impact of the internet. Other stories look further out, stepping out to the stars and exploring what it might be like for mankind to colonize our corner of the galaxy. The outlook of this future can vary from story to story, from hopeful tales of peaceful exploration to cautionary ones where we’ve all but destroyed our own civilization. While most of science fiction takes place in our reality, there are also some secondary world science fiction stories that take place in fictional realities. Some authors write what is known as hard scifi, where they take pains to ensure every detail is scientifically accurate or plausible, while others focus more on the human drama and use the future as a stage in soft scifi. Finally, while science fiction generally starts with the present as-is and posits solely on what is yet to come, some stories might consider how changes to our past might affect our future. To sum it up, defining science fiction is relatively simple, but the ways it can be approached are limited only by our imaginations.

Science Fiction of the Past: The Prehistory of the Future

Since likely before we learned how to use rocks as tools, mankind has been marveling at the points of light in the night sky: the stars, the moon, and the sun. Although what these celestial bodies actually are is common knowledge today, we still look up and wonder what is out there. Even closer to home, mankind is always looking forward to the next innovation, the next revolution, or the next revelation. What the future holds for us is the greatest mystery of them all because the only way to find out is to wait, and if you speculate far enough out, we’ll never live long enough to find out what’s going to happen.

How far into history must we travel to find speculation about the future? One hundred years? Two hundred? What if I said almost two thousand years? In the second century CE, a Syrian satirist living in Roman Greece by the name of Lucien wrote A True Story. This work contained elements common to modern science fiction such as interplanetary travel and alien life. This is considered by some to be the first science fiction story.

In Japanese folklore, the tale of Urashima Tarō describes a fisherman who travels to an undersea kingdom and returns home only to find that hundreds of years have passed. This story appears in several texts, the oldest being the Nihon Shoki from 720 CE, but likely predates this in oral tradition by generations. The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, from the tenth century CE, is another example of Japanese proto science fiction. In this story, a princess from the moon is exiled on Earth until her family comes in a flying machine to take her home.

One Thousand and One Nights is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales first collected in the early eighteenth century. Among them are several stories that could be considered early science fiction, including explorations of lost, advanced civilizations, journeys under the sea, and even travel into space.

Many of these examples stem from folklore or—in the case of Lucien—were intended as satire. However, the renaissance and post-renaissance eras saw great advances in the sciences, leading many to speculate even more seriously on what the future might hold for humanity. Johannes Kepler is one of the most famous astronomers, astrologers, natural philosophers, and mathematicians of this time, most notable for his laws of planetary motion that described the orbits of the planets around the sun. However, even Kepler wasn’t immune to wanderings of the imagination and speculation beyond what mathematics can soundly explain. He wrote Somnium in 1608, in which Kepler himself dreams of a boy who studies astronomy and whose mother summons a daemon which takes them on a trip to the moon. This has been cited by both Carl Sagan and Isaac Asimov as one of the first science fiction books—thought it’s unclear whether they were dismissing Lucien or weren’t aware of A True Story.

The Birth of Modern Science Fiction: Literary Realism and the Industrial Revolution

In the 19th century, an artistic and literary movement called literary realism was a powerful trend that changed the literary arts in dramatic ways. As opposed to the classical methods of telling stories through artistic flourishes and a sense of dramatic style, authors of this movement described reality as it is, down to the minutiae of daily life. By the end of the 1800’s, this movement had become all but a standard. Almost all writers by the turn of the century were taking care to describe the details of ordinary lives in plain language rather than resorting to florid verbosity and Olympian feats of metaphoric diatribe.

This time also saw the results of the industrial revolution changing the very landscape of the world and how we interacted with it. Locomotives turned cross-country travel from a perilous expedition to a daily affair, factories belched out smoke along with mass-produced manufactured goods, and the electric light chased away the darkness of night in a way never before seen in human history. It is no surprise then that despite how down-to-Earth the literary style of the time was, this era also birthed some out-of-this-world stories.

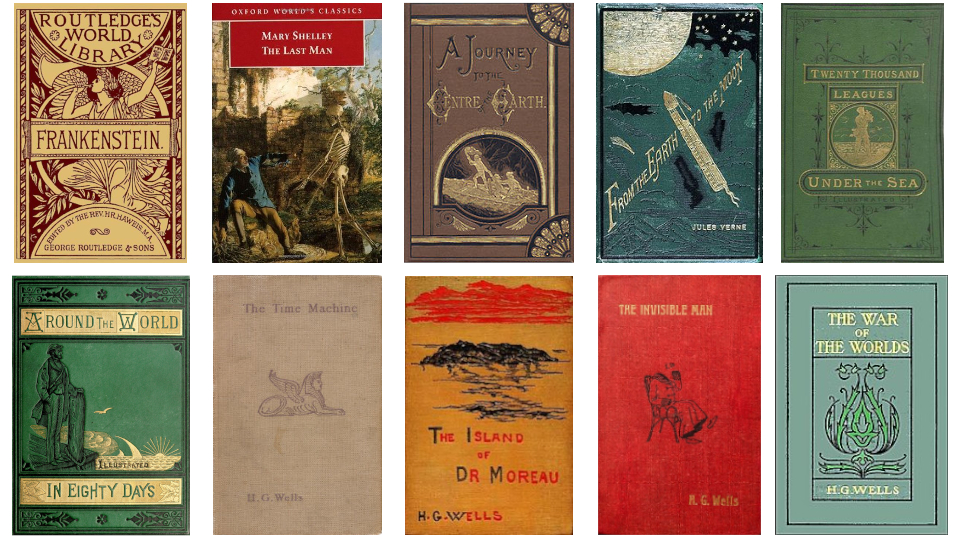

In 1818, Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, a classic tale of a man creating life from what once was dead using science. Considered by many literary scholars to be the first true science fiction novel, this was not her last. In 1826, Shelley also wrote The Last Man, which speculated upon a post-apocalyptic world that had been ravaged by a plague.

Shortly after this, two very prominent authors helped to define science fiction as a genre and legitimize it as a lasting form. The first of these was Jules Verne. The influences of the literary realism movement are evident in his writing, as his attention to scientific detail has been lauded. Among his most notable works are Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1873).

Second of these influential authors is HG Wells, who in addition to writing fiction also wrote non-fiction works predicting the invention of such things as the airplane, military tanks, nuclear weapons, and a concept similar to the internet. His more notable works of fiction include The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), and The War of the Worlds (1898).

Pulp Science Fiction: From Amazing to Wonder

The early 20th century saw a boom in the fledgling genre of science fiction when pulp fiction magazines became a mainstay of entertainment. These inexpensive magazines were a way for the masses to enjoy the pastime of reading in an age before radio and television. Books were expensive, as were traditional magazines, so they weren’t viable for mass consumption. The advent of making cheap paper from tree pulp changed all this. A wave of pulp magazines featuring stories intended for the masses took the first half of the twentieth century by storm, most notably in the US and the UK.

This rapid increase in the volume of words being published provided a platform for many established and undiscovered authors to submit pieces of short fiction, and the rapid pace of both writing and printing offered opportunities for experimentation both with form and genre. Soon, the general public were enjoying tales of weird fiction in the comfort of their own homes and offices.

Hundreds of pulp magazines were published during this era, some running for only a few issues and others for decades. A small handful even survives to this very day, and many publications inspired by the pulps have appeared over the years with varying degrees of success. For the subject of science fiction, among the most influential periodicals from the heyday of the pulps were Amazing Stories, Astounding Stories (later becoming Astounding Science Fiction and eventually Analog Science Fiction and Fact), Planet Stories, Startling Stories, and Wonder Stories (later Thrilling Wonder Stories).

Just a few influential science fiction authors who contributed to these publications were EE “Doc” Smith, Lee Hawkins Garby, Philip Francis Nowlan, John W Campbell, Philip K Dick, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and Sir Arthur C Clarke.

Modern Science Fiction: From Post-War to Post-Modernism

What we’ve explored so far have been the precursors, birth throes, and growing pains of science fiction. We’ve seen that imagining what the future might be like is part of human nature and as old as storytelling itself. Advances in science and technology during the industrial revolution gave rise to the science fiction story as we know it today. And finally, the wide popularity of pulp fiction magazines in the early twentieth century solidified the genre of science fiction as a lasting institution with mass appeal. However, what many consider to be “modern science fiction”—stories that take a hard look at humanity or seriously speculate about the future—really got started in the post-war period.

The Golden Age of Science Fiction

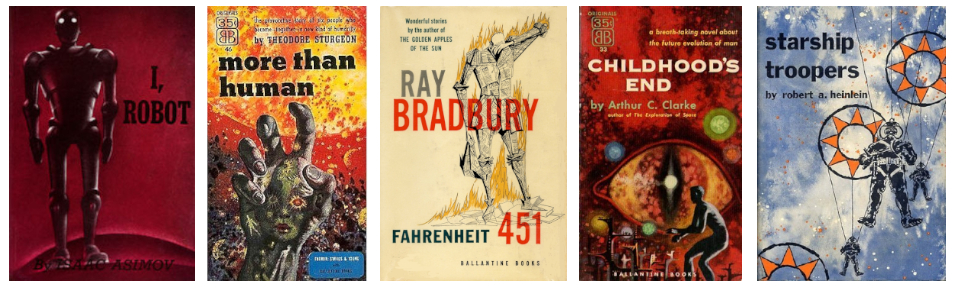

After World War II, the pulps retained their popularity and found a new audience in the form of the troops returning home. This expanded readership led to demand for novels in the science fiction genre—among other genres made popular by the pulps. During the 1950s, authors created groundbreaking works of science fiction such as Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot (1950), Theodore Sturgeon’s More Than Human (1953), Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), Sir Arthur C Clark’s Childhood’s End (1953), and Robert A Heinlein’s Starship Troopers (1959).

Many consider the 1950s to be the “Golden Age of Science Fiction”, as the genre not only gained in popularity but evolved during this decade. While the pure escapism and action-adventure of the old “spaceship and ray gun” science fiction still dotted the shelves, more and more works—such as those mentioned above—began to dive into tackling deeper themes and exploring the human condition through the lens of science fiction.

The New Wave Movement of Science Fiction

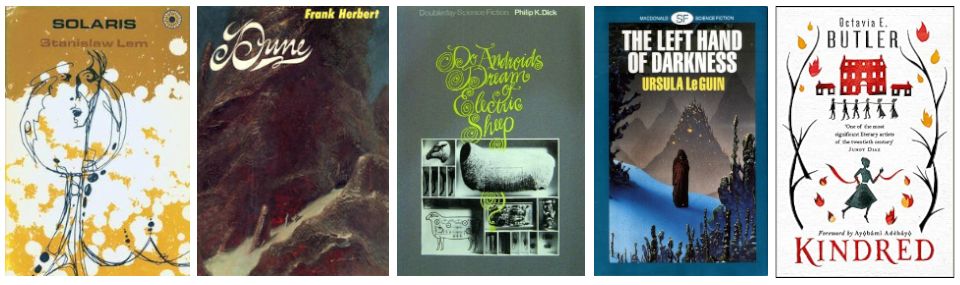

The 1960s and 1970s saw a revolution of more refined literary sensibilities and a tendency to experiment more during what is called the “new wave movement of science fiction”. Many of the works written during this time expanded on the Golden Age trend of exploring social values and examining our place in the universe. Solaris (1961) by Stanisław Lem dealt with the concept of human limitations. Dune (1965) by Frank Herbert was one of the first science fiction works to imagine a complexly detailed and unique future society. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) by Phillip K Dick asked questions about what makes us human. The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) by Ursula K Le Guin was a seminal work of social science fiction which studied the role that gender plays in society. Kindred (1979) by Octavia E Butler is a time travel story which confronts issues of racism, gender roles, and the legacy of African American slavery.

Post-Modernist Science Fiction

The above works might also be considered early adopters of the post-modernist movement, which gained traction in the 1980s. This movement—which crossed lines from literature to art, film, and even philosophy—established a way of thought that promoted skepticism, criticism, and a rejection of established norms and values upon objective analysis.

One of the most famous examples of science fiction during this time is Neuromancer (1984) by William Gibson, which also birthed the cyberpunk subgenre. Consequently, this led to a range of something-punk subgenres that permeate our culture to this day. At the core of cyberpunk and its many offspring is criticizing the status quo for empowering the powerful and disenfranchising the downtrodden. These genres not only question the rules, but often go against them in a literary sense while advocating everything from civil disobedience to outright revolution. While post-modernism is skeptical of established norms, cyberpunk and its offspring often seek to burn them down.

The Future of Science Fiction: Today’s Tomorrow

Since the late 20th century until now, science fiction has remained a strong player in the literary world. Though still chided by the literati, the genre remains a popular source of escapist entertainment and a potentially powerful tool for examining our own societies and the human condition. Themes dealing with pressing modern issues like climate change, economic injustices, and social justice awareness prevail in many works today.

Boosted by the surge in popularity of science fiction film and television over the last twenty years, science fiction literature may arguably be at one of the strongest points in its history right now from a market perspective, relative to other genres of literature. In fact, many of the most popular franchises to hit the screen started on the page, making these adaptations even more of a testament to the lasting popularity of the genre in written form. Just a few examples of twenty-first-century books which ended up on the screen are Altered Carbon by Richard K Morgan (2002), The Road by Cormac McCarthy (2006), The Hunger Games trilogy by Suzanne Collins (2008 – 2010), The Martian by Andy Weir (2011), and The Expanse series by James SA Corey (2011 – 2021).

Science fiction literature has a long history of looking out beyond the horizon and asking, “What’s out there?” This tradition continues today, as well as turning the telescope back on ourselves to peer within and get a better understanding of things like what it means to be human, how we should structure our societies, and what our responsibilities are as caretakers for our home world. Whatever tomorrow may bring, we can rest assured that more great works of science fiction literature will be there to speculate on what comes next.