It’s the end of the world as we know it. (And I feel fine.)

R.E.M.

Post-apocalyptic fiction—or simply post-apocalyptic in the proper context—is any story where civilization as we know it comes crashing to an end. These tales often take place some time after the event that caused this to happen, although some may start with the catastrophe in question before moving on to the aftermath. How long has passed since the apocalypse itself also varies, from struggling to survive the day after to entirely new cultures and civilizations rebuilding thousands of years later. (In contrast, those that focus solely on the apocalyptic event are called simply apocalyptic fiction.)

How the world ends is up to the author, and the specifics of this may play a pivotal role in the overall narrative or simply provide the raison d’etre for the situation being explored. The options include a wide range of events, including pandemics, asteroid impacts, alien invasions, climate change, theological events, zombie outbreaks, tectonic activity, and robot uprisings. The list of what has already been explored is much longer than this, and the potential for new ideas is hypothetically limitless.

Early Apocalyptic Stories

Most likely the first apocalyptic fiction was The Epic of Gilgamesh, written in Babylon circa 2000 – 1500 BCE. In this, the gods send floods to punish humanity. Similar themes of flooding continue through other mythological tales, notably the Judaic tale of Noah from the Torah and the Hindu Dharmasastra. The “Book of Revelations” in the Christian New Testament is another vivid example of early speculation on the end of the world. All these early examples were written in the context of mythology, and it wouldn’t be until much later that secular fiction would pick up the torch that had been smoldering away for some thousands of years.

Bridging the gap is the epic prose poem Le Dernier Homme (in English: The Last Man), published in 1805 by Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville. This work combines elements of the Judeo-Christian Adam and Eve myth with elements pulled from the “Book of Revelations” to tell a story of how the end of the world is an inevitable step along mankind’s spiritual path.

The Last Man (1826), by Mary Shelly (Yes, the same woman who wrote Frankenstein in 1823), is often cited as the first modern example of post-apocalyptic fiction. In this story, several people struggle to survive in a world wracked by plague. This was however only the beginning of a surge in speculation on the theme. Other early examples include The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion (1839) by Edgar Allen Poe, After London (1885) by Richard Jeffries, and The Time Machine (1895) by H.G. Wells.

Modern Post-Apocalyptic Fiction

Perhaps spurred on by the success of the aforementioned works in the late nineteenth century, or perhaps born of a universal malaise in the face of industrialization, economic collapse, and global warfare, the apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic genres grew over the twentieth century to become one of the most popular subgenres of speculative fiction. One must give credit also to the rise of science fiction itself during this time, although this particular niche is notable for its mainstream appeal.

Some prominent examples of post-apocalyptic literature from this era include When Worlds Collide (1933) by Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer, I Am Legend (1954) by Richard Matheson, Alas, Babylon (1959) by Pat Frank, Hothouse (1961) by Brian Aldiss, The Sheep Look Up (1972) by John Brunner, and Always Coming Home (1985) by Ursula K. Le Guinn.

Before long, some of these books were adapted into films. Notably, the release of the adaptation of When Worlds Collide in 1951 was not only part of the golden age of science fiction literature and film, but also a tipping point for the popularity of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction.

This trend would continue over time with the release of such films as The Last Man on Earth in 1964, The Planet of the Apes in 1968 (with assorted sequels and reboots), Dawn of the Dead in 1978 (sequel to the horror classic Night of the Living Dead, and with various sequels and reboots), Mad Max in 1979 (with sequels The Road Warrior in 1981, Beyond Thunderdome in 1985, and Fury Road in 2015), The Day After in 1983, Waterworld in 1995, The Postman in 1997, The Matrix in 1999 (with sequels The Matrix: Reloaded and Revolutions both in 2003), 28 Days Later in 2002 (with sequel 28 Weeks Later in 2007), I Am Legend in 2007, and so on.

And that’s just scratching the surface. When I said apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction had mainstream appeal, I wasn’t kidding. One with a keen eye will also notice several of these films are also adaptations of books.

The Many Approaches to Post-Apocalyptic Fiction

What can one expect from post-apocalyptic fiction? The genre can cross over many other genres, include several common or uncommon tropes, and can explore a variety of themes.

As a genre, post-apocalyptic fiction almost always involves science fiction stories, as they generally speculate on future events in our world. This, however, isn’t a rule of the genre. These stories might also be fantasy if they are set in a speculative secondary world with fantastic elements, such as the Dark Sun campaign setting for Dungeons and Dragons and its accompanying novels. I highly recommend from this The Prism Pentad (1991-1993) by Troy Denning and the Tribe of One trilogy (1993-1994) by Simon Hawke. In this world, magic users draw their power from living things. Through overuse and greed, they have turned a once-lush world into an endless desert.

The apocalypse also suits itself well to horror tales, as evidenced by the widely popular zombie apocalypse subgenre. Films such as Dawn of the Dead 1978 (surpassed by the 2004 remake, in my opinion), 28 Days Later (2002), Shaun of the Dead (2004), I Am Legend (2007), and Zombieland (2009) are among the most notable examples.

One can even mix unexpected genres with post-apocalyptic elements. The Shannara series by Terry Brooks (starting with The Sword of Shannara (1977)) is a standout example of this. That’s right, one of the seminal works of high fantasy from the twentieth century is also a post-apocalyptic story. Although the series follows a relatively formulaic Tolkeinist approach to a fantasy tale (some argue derivatively so), it’s set thousands of years in the future of our own world. After a nuclear war devastated humanity, the new culture that replaced it was a medieval inspired one populated by various races who evolved from mankind through mutations and discovered magic. Post-apocalyptic high fantasy? If that worked, you could probably find anything to mix with it and still have a good foundation upon which to build.

Tropes one might expect to see in post-apocalyptic fiction include the titular apocalypse, a breakdown of societal norms, economic collapse, survival scenarios, conflict over limited resources, the preservation of knowledge, or the search for lost knowledge.

Common themes explored might include the importance of solidarity, the base instincts of mankind versus our heightened sensibilities, the perseverance of nature, the role of government (and the ramifications of its dissolution), the “might makes right” paradigm, and akin to the latter: universal rights versus a meritocracy.

Enjoying the Apocalypse

From different ways the world might end to different genres, a variety of tropes, and every theme one might think of about how to explore the human condition in situations of extreme peril, post-apocalyptic fiction has more variety than one might expect at first glance. What makes the genre so popular? It might be that we all want to imagine how we may handle such a situation if we were to find ourselves in it. Another possibility is that since the prospect of the end of civilization as we know it is something that’s always just over the horizon (especially since we harnessed the ability to cause it ourselves with nuclear weapons), these stories indulge the ever-present fear we have of just such an occurrence coming to pass in reality. In the end, no matter the approach to the apocalypse or why we’re so fascinated by it, the most important thing is to enjoy the end of the world.

My Time in the Sandbox

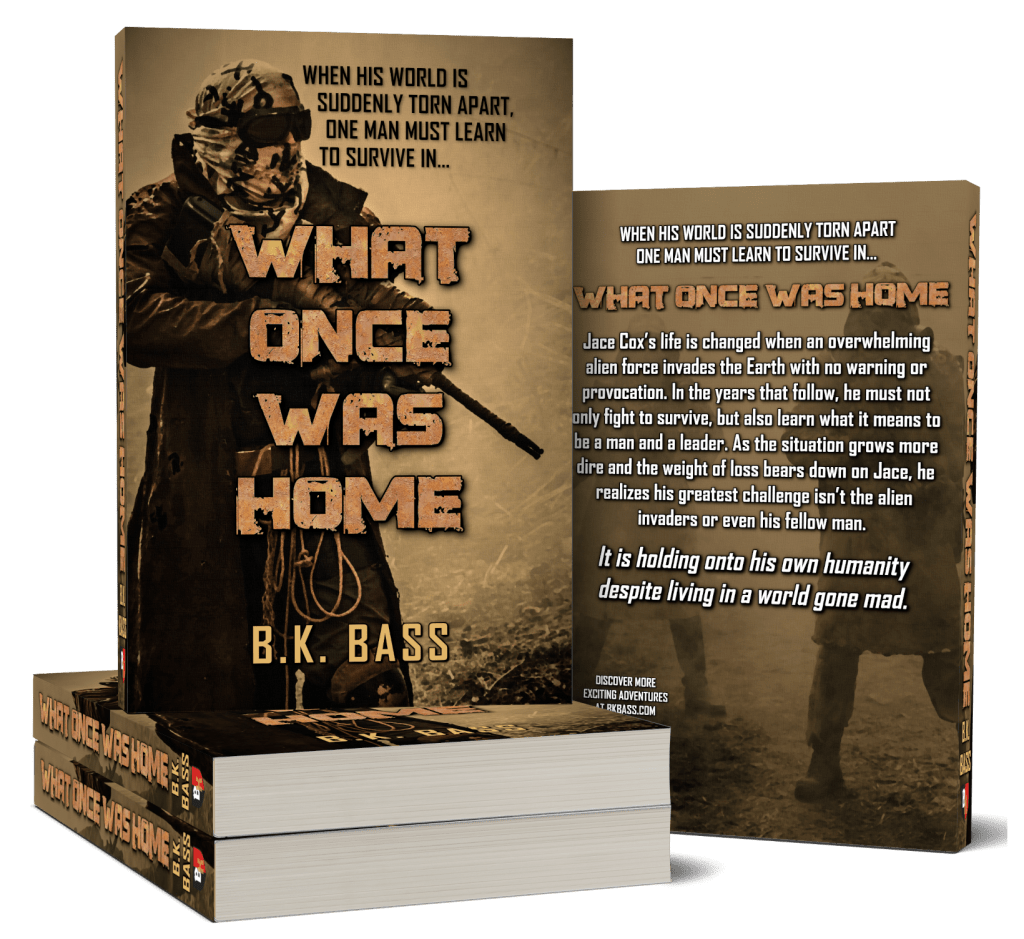

I’ve published my own post-apocalyptic novel: What Once Was Home. The book starts out a few years in the future, and finds a teenager (Jace) having his world torn apart when an overwhelming alien force invades the Earth. The invasion itself is the catalyst of events, but it serves more to set the stage than to be the focus of the novel. In the years that follow, Jace becomes a leader in his community and must not only help to rebuild, but defend it from opposing factions. The story explores themes of community and solidarity contrasted with a “might makes right” antagonist. In addition to this, it delves into personal issues of loss, adaptability, and retaining one’s moral compass in the face of impossible decisions.

What Once Was Home is available now! You can find it in paperback and on Kindle at Amazon or at other eBook retailers.

You may also find this interesting:

Choose Your Own Apocalypse: Ten Post-Apocalyptic Scenarios

We take a look at ten post-apocalyptic scenarios and offer some tips on what to write and what to avoid.